JingPad A1 (DVT) review, part 1

This is the first part of our JingPad A1 DVT review. For the second part, click here.

This is an interesting year for the mobile Linux world. There is a new trend of companies starting to target the consumer market with Linux devices, alongside the usual "hobbyist" niche, be it to escape the Googleverse, or just to try and establish alternative OS standards. That happened with JingOS, a full Linux ecosystem for tablets, and even more popularly with the SteamDeck gaming console just weeks ago. Both projects share a similar technical base: Qt5, kwin and Plasma components, upon which a custom environment is built.

Throughout the past months, we often mentioned JingOS as a Linux-based operating system for tablets. It looked interesting from the start, when we tested the first demo ISOs back in January, and the idea of a family of premium-ish consumer-oriented Linux devices with this new desktop was quite nice to have.

Therefore, when some weeks ago we were offered a pre-alpha developer prototype of the JingPad A1 tablet, the first to be launched (via Indiegogo) on the market, we were happy to accept. Nevertheless, it was agreed that the review would be honest in all its points - not "sponsored", or anyhow biased, so we will clearly try to picture our review from the point of view of someone buying the device for its current price ($549/€454 for Wi-Fi version, including pencil).

Since we would like to go into at least some depth with the review, and you will notice the heft of this part alone as it goes on, we will try to divide it into more than one article, starting from the initial impressions and going deeper into the technical side. This review focuses on our first impressions of the device about hardware and daily (i.e., consumer-like) usability, still taking into consideration that the sample we borrowed is one of the very first prototypes to come out of the factory, and is to be considered pre-alpha both software and hardware-wise. For a fair comparison, think of a PinePhone "Brave Heart" or a Librem 5 "Aspen" rather than the final versions, so some faults are still to be expected.

Hardware specifications

On paper, the device shows some potential. With 128GB of fast UFS 3.1 storage, and a generous 8GB RAM for flawless multitasking, alongside a SoC by Unisoc (ex-Spreadtrum), the Tiger T7510, which is both very new (Cortex-A75) and quite obscure (used only by some new Teclast and Hisense midrange devices, but with no mainline kernel support), but seems to get about as fast as a Qualcomm Snapdragon 845 (used in the Oneplus 6/6T, Poco F1, etc.). The T7510 chip also supports 5G modems, which are sold as an optional to the base JingPad models.

According to UnixBench, the JingPad A1 SoC performs very similarly to the Snapdragon 845 (used e.g. by Oneplus 6/6T).

— TuxPhones (@tuxphones) August 5, 2021

They are both quad-core ARM Cortex-A75, this (Unisoc T7510 5G) is apparently marginally stronger on the CPU side and somewhat weaker on the GPU one. pic.twitter.com/GeX3b1dyB4

The screen also looks promising: a 2K+ AMOLED panel with 4096-level pen input is something unseen on other Linux tablets, and brings this to an upper-midrange Android tablet level. I would like to imagine using Krita for drawing, or Xournal++ for daily note-taking on this device.

The specifications we received correspond to those specified on the page, while the internal component brands written below were derived from our prototype and may slightly change:

- CPU: UNISOC Tiger T7510 (4x Cortex-A75@2GHz + 4x Cortex-A55@1.8GHz)

- GPU: PowerVR GM 9446 @ 800MHz

- RAM: 8GB LPDDR4

- Storage: 128/256GB UFS 3.1 (Micron Technology Inc., MT256GASAO8U21 on our test model), expandable through microSD

- Display: 2K+ (2368*1728, 266 ppi) AMOLED panel, 11", 4:3, 350nit brightness (auto adjustment), 100000:1 contrast ratio, 90% body-to-screen ratio

- Wireless: dual-band Wi-Fi (2.4/5 GHz, 2x2 MIMO), Bluetooth 5.0, GPS/Glonass/Galileo/Beidou, optional 5G modem (possibly V510 baseband?)

- USB: Type-C, with OTG and MTP/U-Disk modes, no HDMI

- Cameras: 16 megapixel (main), 8 megapixel (front), AF, 1.5A true flash

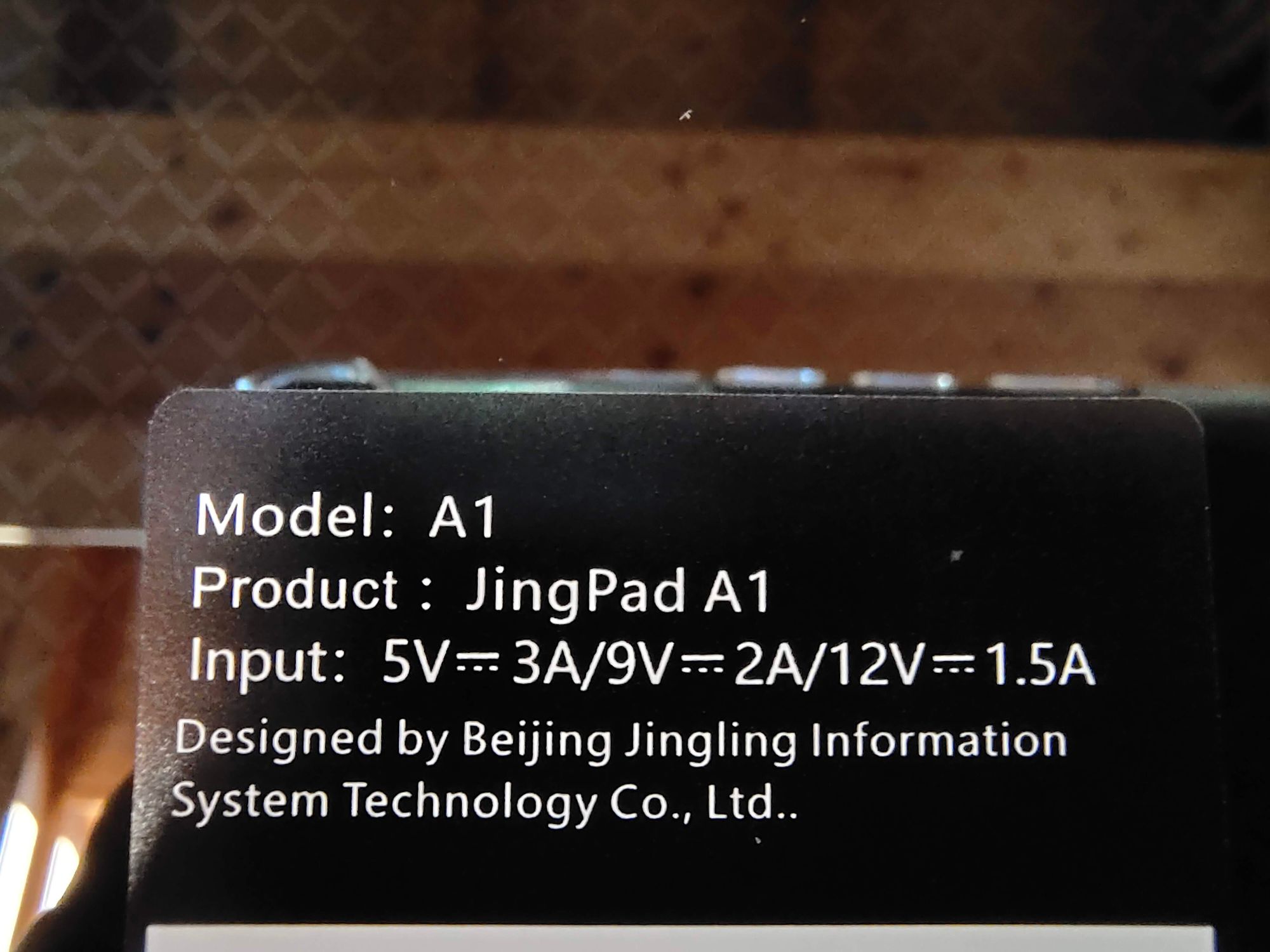

- Battery: 8000mAh (~10 hours of web browsing), 18W fast charging

- Dimensions: 6.7 mm thin, less than 500g weight, brushed metal frame and (Gorilla?) glass back

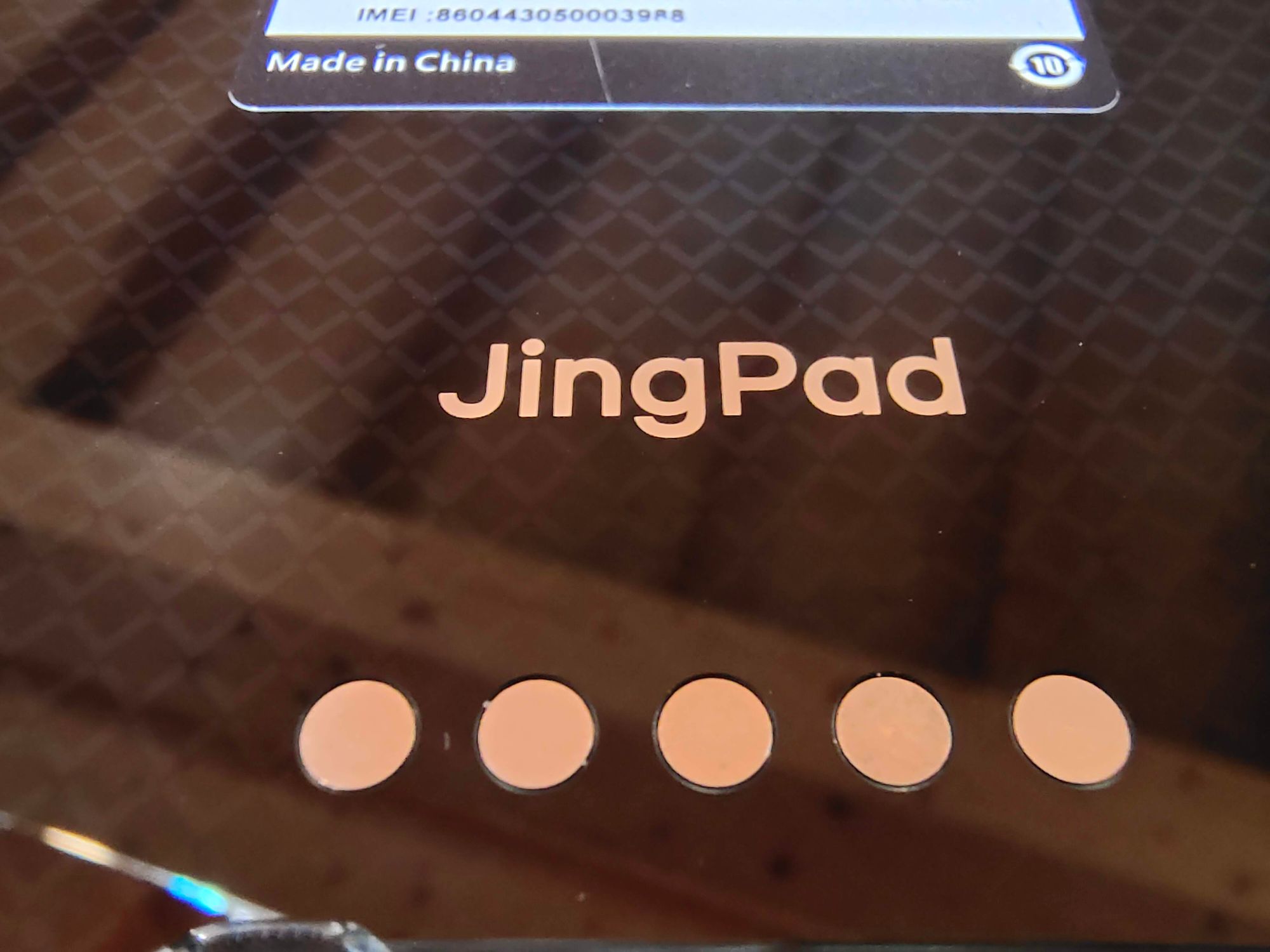

- Sensors: fingerprint sensor (Goodix/Silead?), 6-axis gyroscope, ambient light sensor

- Pen input: supported via optional "JingPad Pencil", 4096 pressure levels (built-in ELAN pen digitizer)

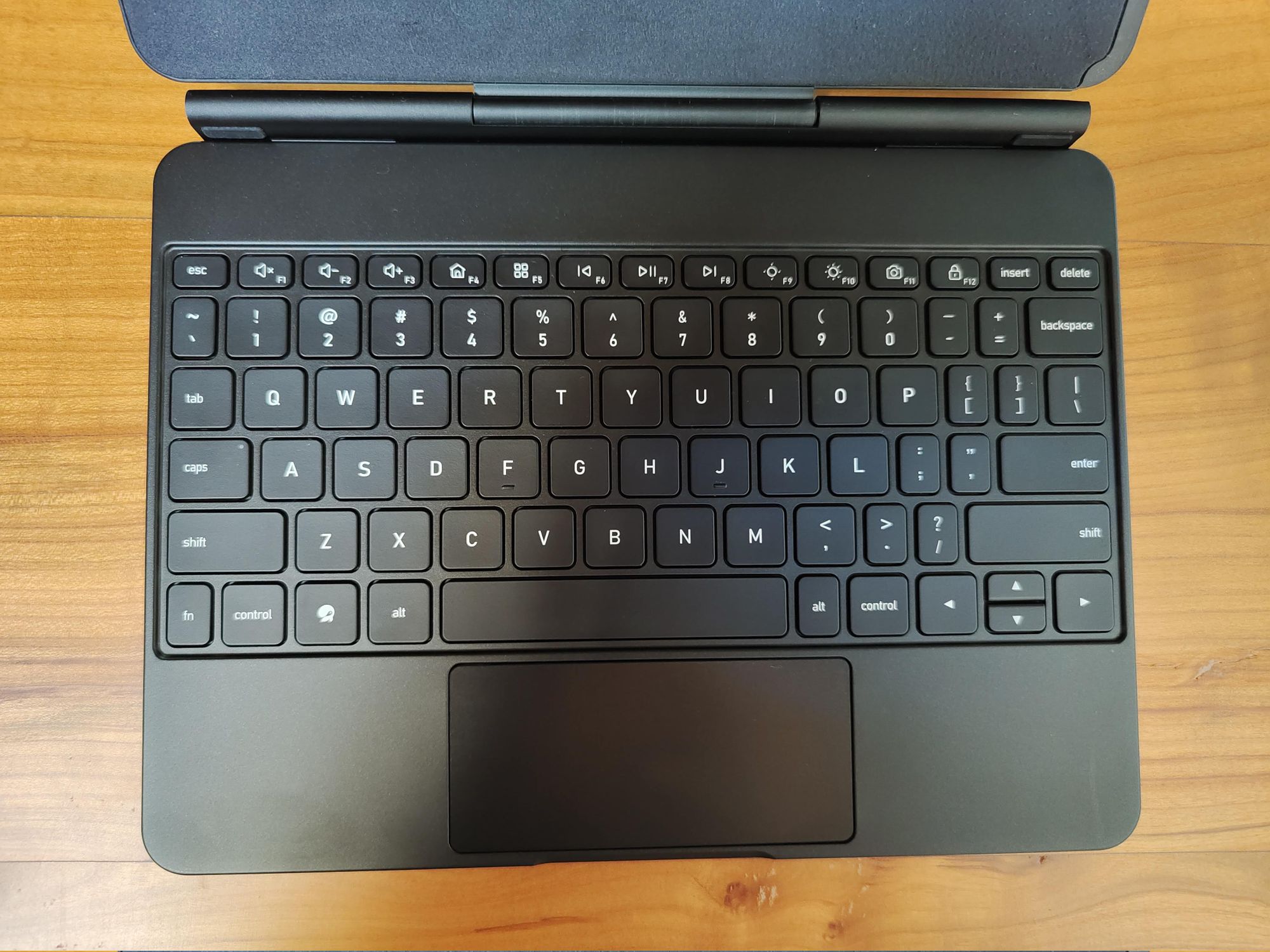

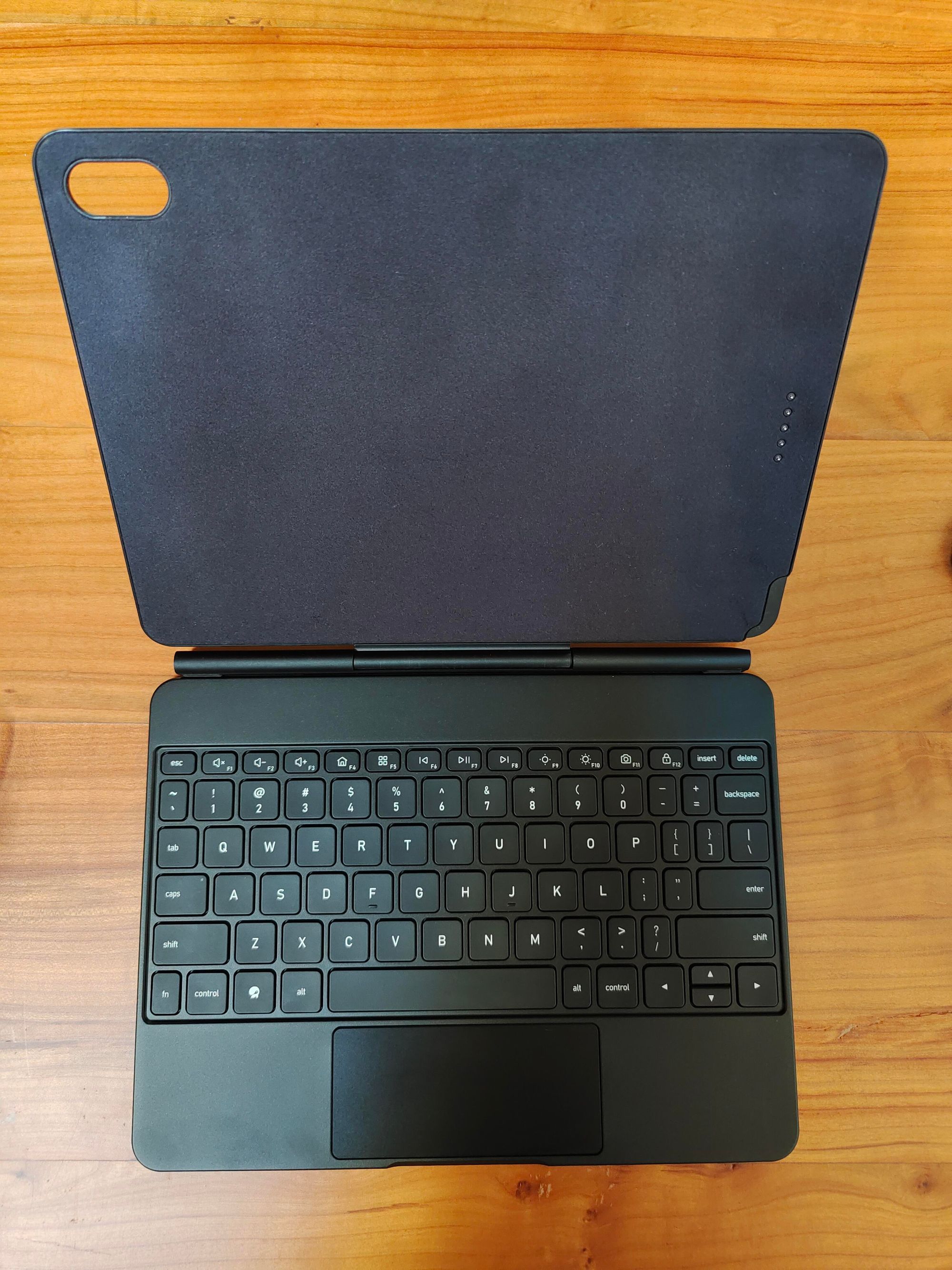

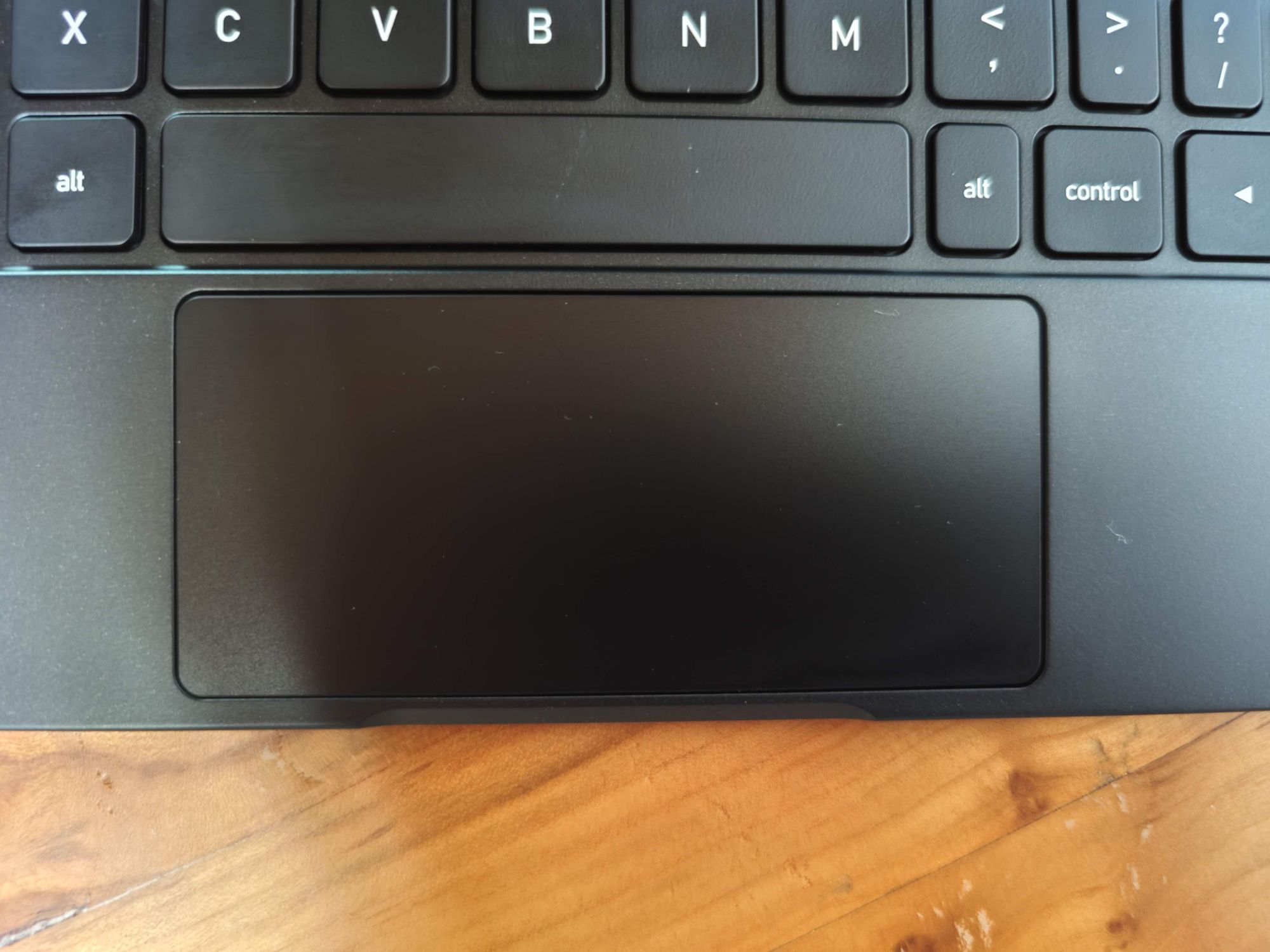

- Keyboard: 11", 6-rows magnetic keyboard with multi-touch (98×45 mm) trackpad, powered via pogo pins

Unboxing - Packaging

After some weeks of delay, partially due to issues with DHL and European customs, a hefty box arrived in our mailbox. It contained the JingPad A1 256GB Wi-Fi version, alongside its magnetic keyboard with touchpad.

As can be seen in the video, the box is quite standard for modern tablet, including a (premium-looking) vegan leather magnetic cover, a fast charger with US plug, a USB Type-C cable (quite thick, so probably rated around 25-30W) and quick instructions and warranty cards.

Notice: The camera used here (ISOCELL GH1 / VIVO X50 Pro +) tends to pick up much more dust and contrast than visible in real life. Since I preferred to leave all pictures unaltered, most imperfections seen especially in macro pictures, such as grains of dust, appear larger than in reality.

Design and build quality

Generally speaking, the build quality of the tablet and its accessories looks impressive at a first glance. The materials feel premium, and the metal frame fits perfectly with the screen and side buttons. The (thin glass) back is solid, and both the leather cover and keyboard quality hardly envy most high-end tablet accessories.

The design of the JingPad is clearly somewhat inspired by the iPad Pro 11, yet moderately original. In spite of the initial marketing, this device thankfully does not feel like an iPad clone, but rather something on its own. [Or maybe I have not used an iPad for long enough?]

Speaker grilles are well placed in the aluminium, and buttons have good tactile feedback. The process used for construction was overall quite ambitious and precise, with the only exception of the power/fingerprint button, which is placed a bit deeper (~1mm) than others, a fault which we were warned about for this particular (DVT) prototype batch and will be solved in production. The power button doubles as a fingerprint scanner using an embedded Goodix controller.

The keyboard cover accessory (sold separately) is sturdy in build, with metal structure and stable pogo pins, so that the tablet is well held and there is essentially no risk of the device slipping out from the cover.

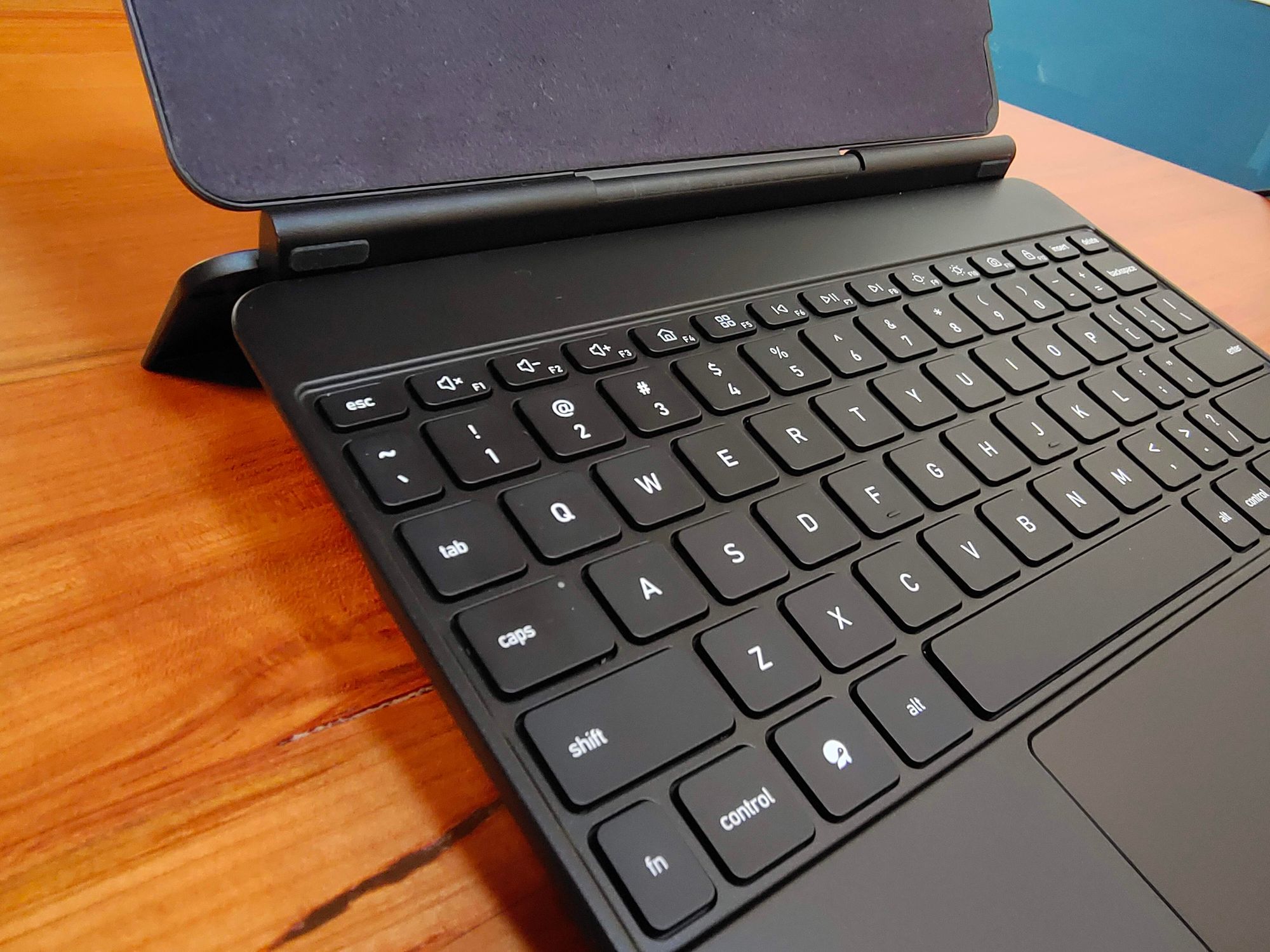

Keys are quite usable, with average/good feel, soft and relatively silent clicking and average (~1.7mm?) travel distance. It feels a bit like an even more compact version of the Dell XPS 13 keyboard, which takes some time to get used to: neither on high-end ThinkPad or Logitech levels, nor cheap in any way. It is interfaced with the kernel directly (via pogo pins), and does not appear as an USB peripheral, but rather as a device-specific node.

The trackpad is tall enough to fit in the bottom row, although it was not implemented in the OS at the time of testing, so we could not assess its qualities. It clicks loudly, but is mechanically balanced, and the "trigger force" for clicks is quite evenly distributed outside the very extremes (corners).

Furthermore, the keyboard has an adjustable base leg to bring it higher than the ground for better stability. I found this "tilting", somewhat mimicking desktop keyboards, quite helpful for typing, but this is a matter of preference. The base is sturdy enough to absorb deep presses and touching without shaking the device.

Does this all justify the $150 price tag for the keyboard alone? I would say it depends. On the one hand, it is a tablet keyboard after all, as are the (overpriced) Surface and iPad ones. And in absolute terms, $150 can get a desktop keyboard with touchpad on a whole new level. On the other hand, the keyboard turns the tablet into an effectively usable 2-in-1 system without any fuss, so the pricing is justified by its careful design.

One important detail to remember, however, is that while the tablet alone is very lightweight (<500 grams), the keyboard takes well over this weight, probably somewhere around 600 grams alone. So the result will look like a small laptop in your bag rather than the thin tablet it was before.

Anyway, the tablet's magnets, used for attaching the covers, are strong. In my sample, they were strong enough to safely attach the thing to any metal surface, like... say... my fridge. All of this provided that you have an easy enough way to take it off afterwards.

First boot and display

The boot time, from zero to lock screen, took between 33 and 37 seconds in our tests, which is on the good side for mobile Linux devices. The AMOLED screen looks bright and clear, with very good (2K+) resolution and wide viewing angles, in spite of a temporary (font? UI?) issue downscaling it to 1776 x 1296. This, however, was an acknowledged issue which was promised "to be solved in production models".

In general, the user interface reminds of Chrome OS, both in layout and philosophy (i.e., a Linux overlay with good Android integration), but overall more open (e.g., obviously providing root access, custom repositories and any kind of app installs) and complete. Esthetically, it reminds a lot of both Huawei's EMUI skin and, of course, Apple's iPad OS.

UI components are quite modern, with split "notification center" and "control center", apps can be moved between pages (although not yet searched or gathered in folders), and multitouch gestures implemented at KDE/kwin level make usability possible even in edge cases like frozen windows or full-screen apps.

The UI is overall smooth, although never reaching the heights of 60fps animations, rather establishing itself in the 35/45fps range. I guess this has to do with GPU drivers, since very similar problems were encountered e.g. on the earliest Librem 5 and PinePhone models, before good, open-source GPU drivers were developed. Also, since the Android GPU driver is currently piped through libhybris due to the downstream kernel, this may also be affecting the performance.

Running a quick glxgears as benchmark, frequency is reported around 60fps with VSYNC enabled, but it does not feel like 60FPS, probably due to GPU dropping some frames, and some light tearing is visible between the moving cogs at times. On the other hand, the 40FPS-ish range seems to be stable also on games like SuperTuxKart, which the GPU itself should be able to handle without issues.

Bootloader and Flashing ROMs

Clearly, the bootloader is totally unlocked by default, and the internal memory can be flashed with any ROM without hassle. I did not fully understand the flashing procedure yet (which is the standard one for UNISOC devices, and involves a bunch of .exe files and Bash scripts), but it can be accessed with a key combination at boot time.

While no third-party ROM alongside JingOS exists for this device at the moment, a secondary Android ROM with Jing-like user interface is also being developed for this device, but dual-boot is unlikely, and I do not know if we will be able to test it as well in the next months.

Software

JingOS runs on a desktop environment named JDE (Jing Desktop Environment), which is based on KDE Plasma Mobile and kwin. This choice exploits a mature software stack, with Qt5 supporting hardware acceleration and touchscreens, and a wide community of developers. In the past months, we were (informally) told by some Plasma Mobile developers that there exists some upstream collaboration between the Jing and KDE teams, so it is not just a silent, more gesture-oriented fork of a popular project. Sources for most of the UI are already available on Jing's GitHub, although tsome will be released alongisde product shipping in the next months

Multi-tasking is handled well by the large amount of RAM: playback of full HD content from YouTube in Chromium while writing documents in LibreOffice is an effortless task, and a large number of open windows does not seem to visibly affect the performance of the drawer.

While most apps are as expected, not all software works out of the box. Due to a mix of reasons, like conflicting toolkits (ah, Linux), scaling and kwin handling of components like GTK about dialogs, there are some apps that are not yet installable, at least through the official "app store", or entirely usable on the device.

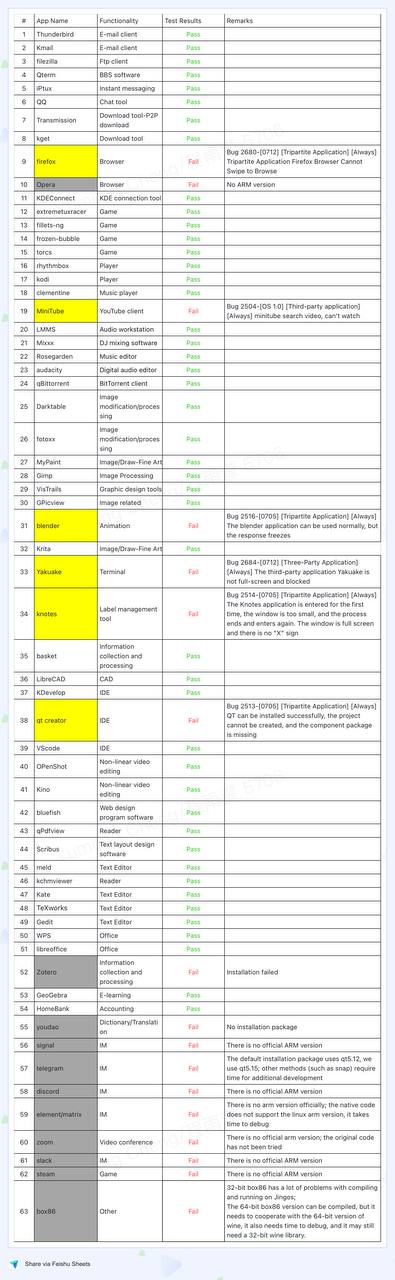

The good news is, not only most software works, but there is a somewhat detailed table on expected support of many applications dating back to last month already, and most of these applications seemed to work fine (excluding, in some cases, the missing on-screen keyboard popup) in our tests.

Our first impressions were of having two layers of support: Android and Jing/KDE apps on top, and minor toolkits needing further polishing. It seems like some manual adaption of applications like LibreOffice was done to adapt them to become usable on JingOS, yet toolkits like GTK are somehow less supported by the Plasma Mobile enviornment. Scaling issues in apps like Gedit are made less visible by the large screen size, but expect some smaller fonts in areas of the UI. However, it is quite likely that more work will be done to bring the "GTK half" of Linux applications to JDE/Plasma Mobile before release.

The tablet runs on the original, downstream 4.14 kernel fork provided by the manufacturer for this chip's Android ROMs, which is far from being a mainline branch.

# uname -a

Linux localhost.localdomain 4.14.133-1626560274+ #89-JingOS SMP PREEMPT Sun Jul 18 06:27:57 CST 2021 aarch64 aarch64 aarch64 GNU/LinuxIn fact, not running on a mainline kernel has some relevant complications. The Android kernels tend to become unmaintained, apart from Google-delivered "security patches", and do not have the level of high-quality support that the Linus kernel tree allows. In this case, a libhybris compatibility layer is needed above the kernel to bring things like Android GPU driver support to the Linux userspace using API abstractions. So, while the OS speaks Linux and is technically Linux, it is a more layered and messy code base than that of pure, "mainlined" devices. This is also the case of most officially supported Ubuntu Touch and Sailfish OS devices, which tend to use either Halium or libhybris above the Android kernel instead of supporting the "mainline" tree.

While this issue is technically solvable, the process of mainlining a new chip like the UNISOC T7510 takes months and considerable investments, which we are unsure we will see on this device.

User Interface usability

The UI is quite complete from an usability point of view, and proved to be relatively stable in our initial tests, apart from some crashes and freezes, which it was able to handle gracefully most of the time.

The only edge cases that made it stranger were after enabling the official Android app compatibility layer, which essentially brought some UI components from the secondary Android image into the system, but that is probably more of a temporary bug than an architectural fault, considering that Android app support (or Jing's android-compat package, as apt calls it) is only 2-month-old.

Occasional UI hangs occurred in the first days of usage, if anything to testify the pre-alpha nature of software, but all resulted in automatic reboot of the desktop without real panicking.

One common question is: can one easily change UI on this tablet, e.g., drop JDE altogether and move to vanilla GNOME or KDE? The answer is, theoretically yes, but this will likely imply dropping the Android compatibility layer and integration with most UI components, so it would be wiser to imagine this product as best suited to the JDE / KDE Plasma ecosystems, and other environments as external, unsupported experiments for the time being.

Regarding the UI, the most obvious comparison that comes to mind is with Deepin: both are Chinese in origin, both have something tablet-esque Apple vibes, and both aim at the customer market rather than hobbyist niche. So how do they differ between each other? Firstly in their target, since Deepin is an older laptop DE which just recently started eyeing touchscreen support.

While Deepin can boast a larger community and more mature code, the feel is that the stack could be more technically solid in JingOS in the long run, since no cocktail of UI toolkits and libraries is seen (Deepin uses a mix of custom-themed Gtk3 and Qt5), but the focus is rather on Qt than GTK apps for the time being.

Summary

As you may have noticed, this review did not get into much depth about the actual usability of single applications. Since we would like to have a bit more testing before drawing any judgement on this side, we will leave that to part 2, which may take a while to write.

As a side note, we contacted the technical support team of JingLing quite often on Telegram to solve some issues (e.g., with setting up the Android compatibility layer), and they have been extremely friendly. So, provided that they manage to be as welcoming to all users, this would be a nice plus for the company.

We will continue this series with our second (and hopefully shorter) review, going deeper both into real-life usability (Linux and Android apps) and technical tests about more hardware components.

| Pros | Cons |

| + Premium build | - Messy downstream (Android) kernel |

| + Modern specs | - No HDMI output |

| + Consumer-oriented | - No headphone jack |

| + Android app support | - (Still?) limited repositories |

| + Smooth software | - UI still pre-alpha |

| + Excellent keyboard cover | - On-screen keyboard not always showing |

| + Drawing capabilities | |

| + Long battery life | |

| + Optional 5G broadband | |

| + Good camera sensor | |

| + Loud speakers |

Initial verdict: The JingPad A1 is a surprisingly usable mobile Linux device, which looks at the consumer market while actively involving the hobbyist niche. If the lack of mainline kernel or open-source GPU drivers does not directly bother you, this is probably the most modern Linux tablet you can find.

Jingling is selling the JingPad A1 on Indiegogo (until August 15th, 2021), and told that retail price after the campaign is still to be fixed.

Comments ()